Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

On WA-20 west toward the Anacortes Ferry Terminal, Michael and I found a Spanish radio broadcast with news relayed at a curiously slow pace, so that even we, with our limited Spanish, could understand. It was a multicultural station based in Vancouver. We got news of sex trafficking in Buenos Aires, corruption in Brazil, and an interview about traditional foods in a certain town in Mexico whose name eluded me: horchata tamarindo, pavo, taquitos fritos, plus socializing at church. There was mariachi music, then a pan flute.

In the next hour, the language switched to something I couldn't recognize. Something Scandinavian? South Asian? I had no clue. But then bhangra music came on, so maybe it was Punjabi?

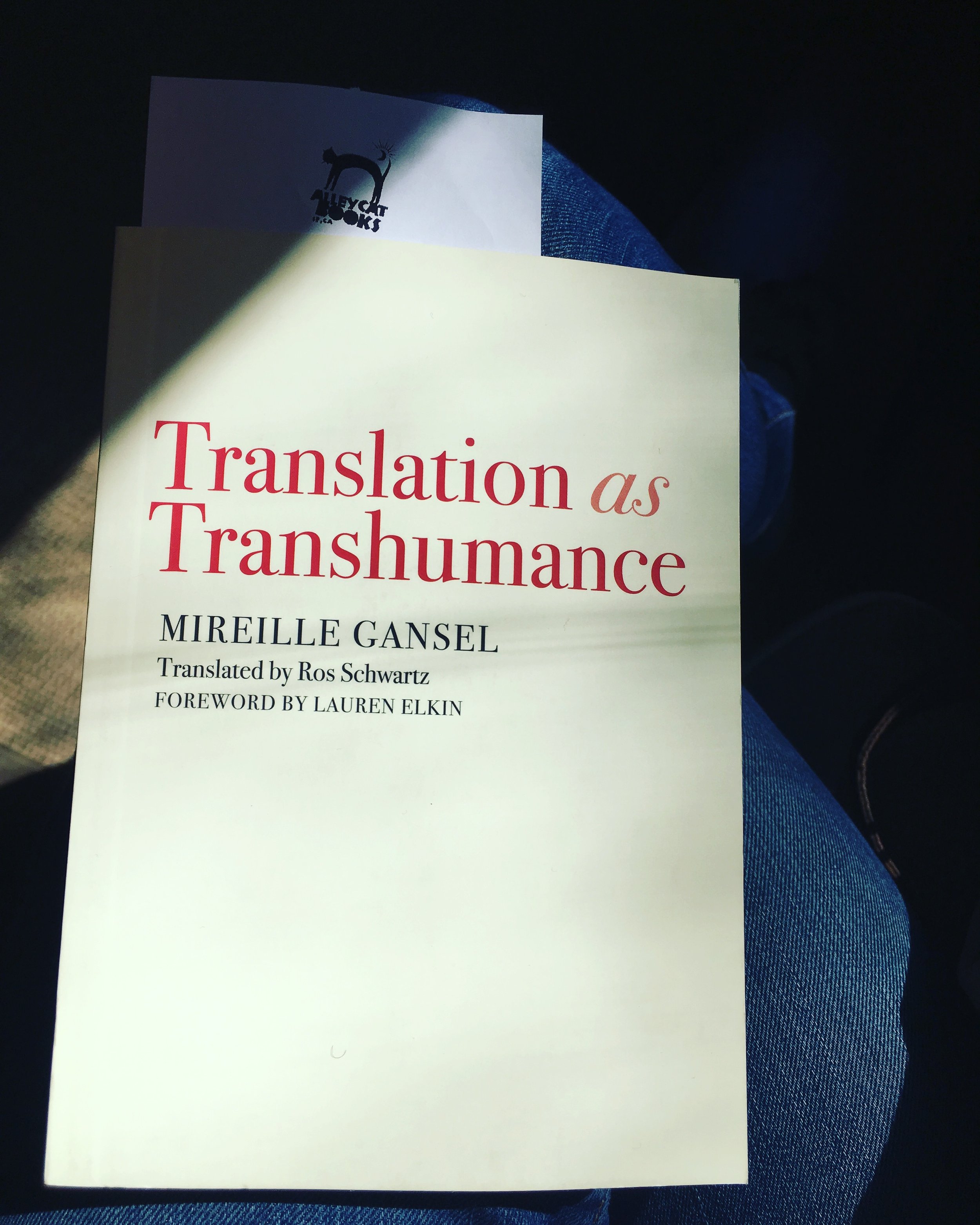

At the ferry checkpoint (we were on our way to Victoria, British Columbia), I lowered the radio, as if customs would find foreign sounds questionable. Once we were on the boat, I switched my phone to airplane mode and concentrated on Mirielle Gansel's Translation as Transhumance (trans. Ros Schwartz), which Michael found at Alley Cat Books in San Francisco, when I was there on book tour in April.

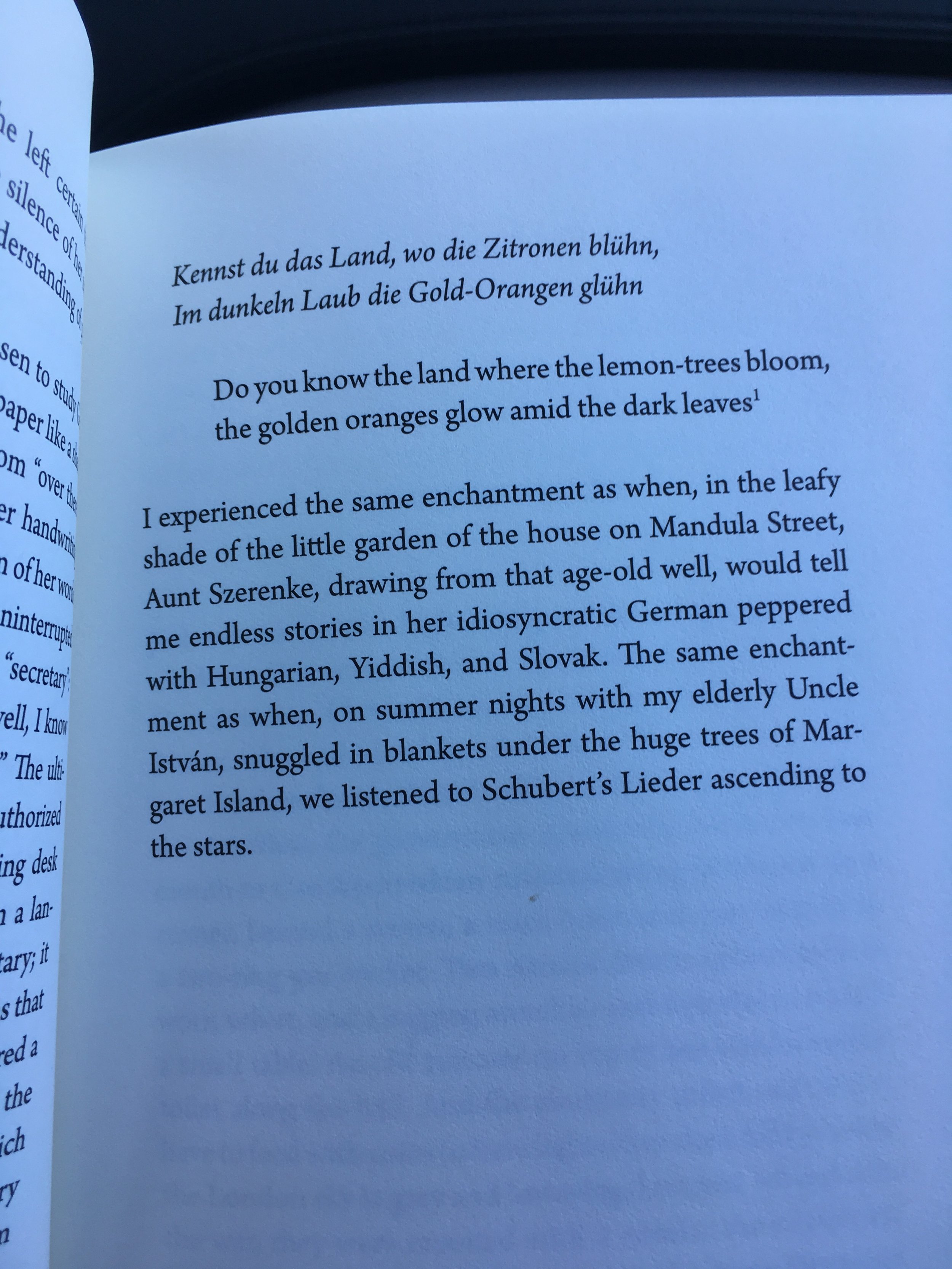

It seemed appropriate to read a memoir and philosophical treatise on the act of translation while crossing into Canadian waters. Gansel's family survived the Holocaust; she grew up in France and remembers the special occasions when a letter would arrive from Budapest and her father would solemnly translate it aloud. Some of her memories remind me of visiting Freiburg, Germany with my grandmother, who spoke a mishmash of Romanian and Hungarian with her cousin and uncle (they saved Hungarian for dirty jokes), and where the cousin's husband spoke German and their children spoke English to me. Here is the lovely excerpt which prompted my reverie:

In the 1960s and '70s, Gansel went on to translate poets from East Berlin and Vietnam. Something she touches upon which I would like to research further is the "de-Nazification" of German and the attempt to translate Vietnamese poetry without exoticization. She mentions Bertolt Brecht de-Nazified Hölderlin's translation of Antigone without comparing examples. But she does offer this translation of poet To Huu (translated into English, in turn, by Ros Schwartz--oh, the layers!):

Casuarina forests,

Groves of green coconuts,

The shimmering of the white dunes

where the sun trembles,

garden of watermelons with red honey!

Gansel quotes Nguyen Khac Vien, who invited her work to on an anthology of Vietnamese poetry in translation: "Exoticism arouses simply a sense of foreignness, without being able to communicate the emotions, the deeper feelings that inspire a work."

On that notion of digging for deeper feelings, Gansel shares her approach to translating the entire oevre of Nelly Sachs, a Jewish German-language poet who lived in exile in Sweden. She ended up rewriting the work four times, using the Bible's four levels of meaning, according to the Jewish tradition of exegesis: Peshat (literal meaning), Remez (allusive meaning), Drush (deeper meaning), and Sod (secret, esoteric meaning).

I could go on and on and on about how much I love this slender volume about exile and empathy. This book has opened so many doors for me.

The Seattle Public Library and Seattle Arts & Lectures launched

The Seattle Public Library and Seattle Arts & Lectures launched

August is

August is